Stanford is the Top-Scoring Institution for Sustainability Under AASHE STARS 3.0

The university earns STARS Platinum in version 3.0, the highest score under the sustainability rating system.

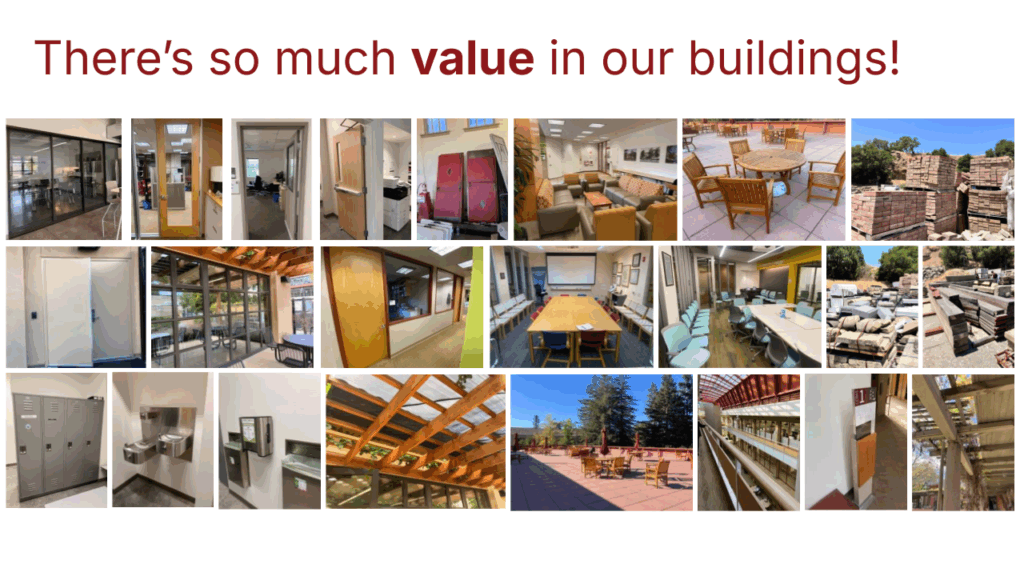

There is significant value in buildings (carbon, cost, historical significance) that is lost when the business-as-usual approach of demolition and rebuilding is continued. Existing structures are rarely assessed for reuse potential, and life cycle analyses often overlook this potential. Demolition fills landfills and perpetuates the use of increasingly scarce and expensive raw materials. In contrast, deconstruction and salvage reduce emissions and waste, retain the value of materials, and reduce the environmental burden from the built environment sector.

Reuse can be implemented at all stages of a project’s life cycle. Once a building is slated for demolition, salvageable materials should be inventoried and deconstruction planned to maximize recovery. During design and construction, teams must intentionally incorporate salvaged materials into design, cost, schedule, and logistics.

To normalize material reuse, all stakeholders must support the process. One of the biggest challenges is the culture shift from defaulting to demolition to valuing deconstruction and salvaged materials.

Logistically, lack of coordination, documentation, storage, and a central inventory make reuse difficult. Projects also face added costs, liability concerns, and few incentives. Designers struggle to plan for reuse without early knowledge of available materials, and contractors favor fast, unsorted demolition to meet schedule and budget goals. Deconstruction experts often join too late. Most buildings aren’t designed for disassembly, and older ones often contain hazardous or non-standard materials, reducing reuse practicality. As an emerging market, efficient reuse infrastructure is limited, so shifting mindsets across all roles is key to making reuse standard practice.

Since reuse is new to Stanford’s project delivery process, the team has been learning by doing across different projects. A major part of this work involved engaging stakeholders to understand their roles and challenges. It was found that reuse varies by project and by material. The first step was identifying all considerations: cost, carbon, and reuse practicality are main factors, but also how reuse influences maintenance, risk, and aesthetics. This then led to logistical discussions on who handles inventories, storage, transport, deconstruction, and demolition; when to claim salvageable materials; and how to align timelines and storage durations.

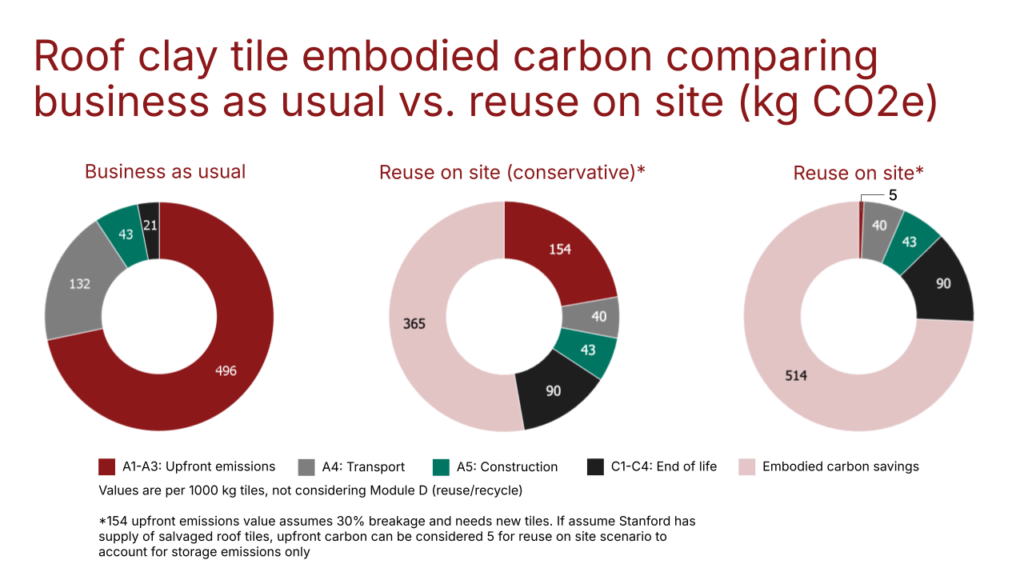

For embodied carbon analysis, the focus was on upfront carbon as the main driver for savings in a reuse scenario compared to buying new, since this makes up most of a material’s emissions, though reuse also reduces transportation emissions.

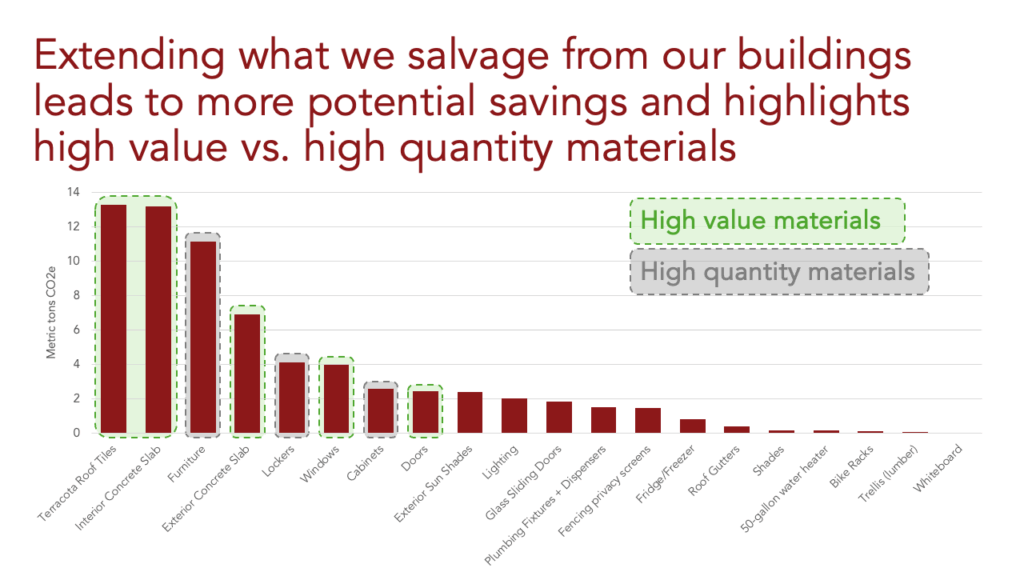

On-site reuse leads to significant carbon savings, particularly in upfront carbon from avoiding new material extraction. As deconstruction and reuse are new at Stanford, materials were categorized by reuse priority: strongly recommended, strongly considered, case-by-case, and not recommended. Factors included embodied carbon intensity, reuse risks (such as labor, breakage, and lifespan), and quantity.

A campus project reusing clay roof tiles showed a 92% emissions reduction compared to buying new. Another project explored reusing windows, doors, fixtures, furniture, lumber, concrete, and more—potentially diverting 390,000 pounds of waste and 68,000 kilograms of carbon. This pilot helped the team evaluate materials, plan reuse timelines, and identify key stakeholders. It also highlighted considerations for designing new buildings with salvaged materials and laid the groundwork for integrating reuse into future projects.

First, deconstructing and reusing ‘strongly recommended’ materials should be normalized, specifying them to prioritize reuse before buying new. For other materials, clear metrics and a decision-making process should be created to guide reuse per project, with all best practices documented. Designing with salvaged materials should become intentional, accepting some mismatches as part of reuse. To proactively address future reuse, new buildings should also be designed to be more easily disassembled.

PRIMARY PARTNER: Land, Buildings & Real Estate

Adeline Leung is a 2nd year Master’s student in Sustainable Design and Construction. She has previously worked on the design and construction of transportation facilities, as well as researched the embodied carbon abatement and storage potential of bio-based building materials. Her interests lie in regenerative design, adaptive reuse, and sustainable materials, and she hopes to integrate architecture, engineering, and construction to implement sustainable solutions in the built environment.

The university earns STARS Platinum in version 3.0, the highest score under the sustainability rating system.

Stanford’s Travel/Study programs are leading a quiet revolution in climate-conscious cuisine.

Stanford Travel/Study, an educational travel program for alumni and friends of the university, is tackling plastic waste trip by trip.